Two places, two wells and a case of mistaken saintly identity…

April 2020

A bright Saturday, a week into the lockdown. We walked south out of Athenry on the Craughwell road, then branched off towards Kiltullagh by the graveyard with its tight ranks of crosses. The afternoon light had that new expansiveness that comes in the first days after the clocks go forward, and the glossy ryegrass was shivering under a choppy breeze. Past the builders’ merchant and the first few bungalows, we clambered over a field gate. Cara set straight off up the low rise, but I held back.

“Come on! It’ll be fine!”

“Well, you do the talking, if we get caught…”

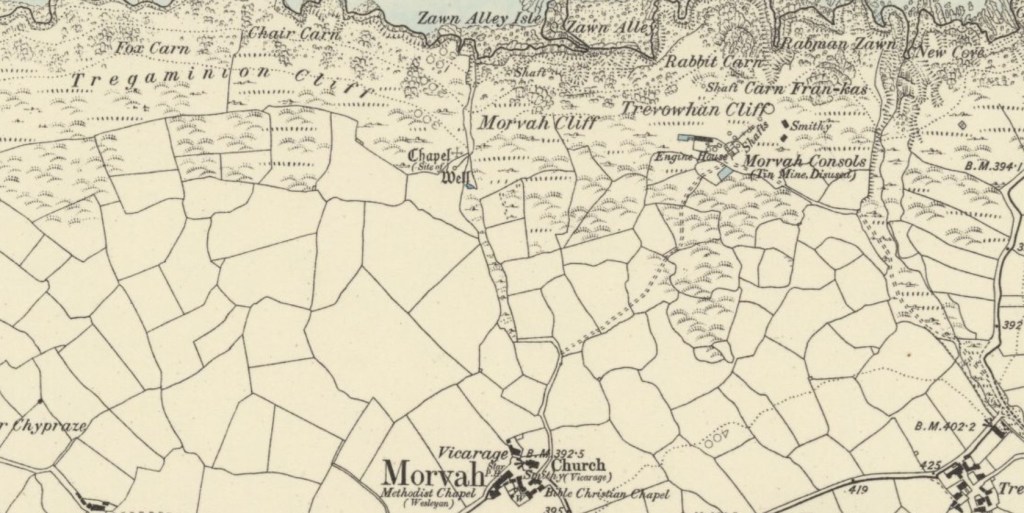

Walking onto farmland in Ireland always made me uneasy. At home in Cornwall I’d wandered any which way without concern since childhood. I knew, without ever having had to learn, who held each acre in Morvah parish – and knew that they knew me. Running up to the edge of the moors beyond our own little holding: Rex’s fields (which became Terry’s, later bought out by the National Trust with Guy as tenant). To the cliff side: Willie’s land (then Susan’s, leased to Robert); the same arrangement in the little triangular projection running out towards Morvah Churchtown. Over the brow to the southwest: the Hichens’ mixed acreage. Then on the levels to seaward again: Tregaminion land, the Jaspers’, running into what had been Dorothy’s smallholding and was now Mervyn’s. Back east, hidden behind Watch Croft’s rough northern flank: the web of little fields at Rosemergy, laid out on Iron Age and even Bronze Age templates, a long-standing National Trust holding, tenanted by Maisy, later Bob. I could carry it on over the parish boundary too: Arthur’s; the Greens’; Frank’s, John’s. And for the nearest fields, I could even take it backwards to a generation before my birth: Tom Pearce (a tenant of Old Man Charlie Bone at Bosiliack in Madron parish, himself on a multigeneration tenancy from the Bolithos); Matty Mann; Freda Tonkin; Bernard Trewern (the last two old folks in my childhood; the others dead long before my birth).

But I had none of those references here. I couldn’t match a single field to a farmhouse. There was something else too: if I did happen to stray from the footpath beyond my home parish in Cornwall, or even in Leicestershire, I was always happy to talk myself right should I run into the landholder. But in Ireland history intruded, and if there was a particular jealousy around land here, then history surely had something to do with it. An anticipated cry of “Get off my land” had special contexts, and though I might call myself “Cornish” in Britain, my tongue was plainly branded with a different word here. The few times in the past that we had run into a farmer, telling us firmly that we were on private land in the Burren or Connemara, I’d sheltered behind Cara like a shy child. The fact that fully half of the progenitors whose trickling bloodlines would eventually coagulate as a baby boy in Penzance were themselves Irish when the worst of the history was happening only added an incoherent irony to the anxiety.

But Cara was already over the next wall.

We dropped down another slight slope into a shallow bowl of farmland. To the left lay a stretch of low, boggy country, perfectly flat. Beyond it, a few cars span around a roundabout, and further off the roofs of the retail complex between the little Clarin River and the GAA pitch were catching the sunlight. Another uphill stretch, a scramble across a couple of big walls, and suddenly we were in a little wooded patch, fenced off from the surrounding fields. There was a disused badger sett in the roots, and a ruined cottage, half thatched with ivy. The lintel over the wide hearth had snapped, but a tight plait of ivy roots still spanned the gap. Who had lived here? When had they left? Neither the place itself, nor any of the answers, was indicated on the modern OS map.

Beyond the ruin, an overgrown laneway, tangled with brambles and new-sprouting nettles. It brought us out, with a sense of small victory, at Lady’s Well, where a man was praying at the grotto under a blueish statue of the Virgin. We gave him a solid two-metre clearance and sat down on one of the benches.

The well complex didn’t have the feel of an ancient place – less so than the ruined cottage, hidden in the trees fifty metres to the south. There’s a well here, marked as “Toberblanra” on the 1838 Ordnance Survey map, but the grotto was built in the 1950s during a nationwide bout of enthusiastic Marianism. The carpark and the flowerbeds and the grey statues were put up in 1999 to mark the new millennium. But an Assumption Day gathering was an old thing here. In the early twentieth century they laid on special trains from Galway each August to carry the hundreds of pilgrims from Connemara who travelled east for the day into this greener, softer country.

The standard story dates Our Lady’s association with the well to 1249, when a Gaelic army attacked the Anglo-Norman occupants of the new town. The attackers were defeated, and as they retreated past the well the Virgin materialised to tend the wounded stragglers. If the well had a genius loci prior to 1249, its identity is unknown. But I have my suspicions.

There is a holy well in my home parish too. It is hidden in a triangle of brambles, just off the coast path. As in other Cornish parishes, the well and the little chapel that once stood alongside it were the precursors to the church that now stands five hundred metres to the south. But there’s something peculiar about Morvah: the church – a plain nineteenth-century granite shed bolted onto a more elegant fifteenth-century tower – is dedicated to Saint Brigit of Sweden. The idea that a Scandinavian holy-woman might have ended up with a foothold on this Atlantic coast is strange enough to begin with; in the wider context it is downright bizarre. Every other parish in the vicinity – almost every other parish in Cornwall, in fact – has as its patron one of the so-called “Celtic Saints”. These men and women – a handful plainly historical, the bulk of them decidedly apocryphal – emerge from the post-Roman murk. Many, according to legend, were Irish: Piran, Ia, Buriana, Euny, Erth; a veritable armada of whey-faced holy-bodies forging south across the Celtic Sea aboard miraculously buoyant millstones and giant oakleaves.

So how did Morvah, one of Cornwall’s most isolated parishes, get lumped with a Swede? A small amount of detective works straightens things out. The earliest known record of a chapel on the clifftop beside the holy well dates from 1390, when it was already associated with a “Saint Brigid”. Birgitta Birgersdotter, the Swedish Brigit, had been in her grave a mere seventeen years at that point – and crucially, she still had a year to wait before canonisation. Morvah’s original dedication, then, must have been to the much more obvious candidate: the fifth-century Brigid of Kildare, she of the cross of bent reeds that hangs inside many an Irish home. At some point between 1391 and the 1820s, a minor canonical confusion must have arisen – perhaps a simple spelling error. And suddenly a flaxen-haired noblewoman from Uppland finds herself transported to a wind-lashed farming community at the edge of an ocean. “Wait,” she cries; “There’s been a terrible mistake! I’m Brigit with a T!” But none of the baffled locals speak a word of Swedish…

But there’s more. Brigid with a D – the Irish Brigid – is the patron of boatmen and sailors and brewers. She was able to turn water into beer. The reeds for her cross sprout from the soggiest of places. She is a very wet saint. In fact, beneath her Christian robes she bears a remarkable resemblance to her older namesake, a goddess associated with fertility. The Christian Brigid’s feast day – 1 February – is a rebranding of the Pagan Brigid’s spring festival, Imbolc. And that cross of reeds, good to protect the home against all disaster – surely it looks less like a crucifix than some other, older charm.

Pagan Brigid was not exclusive to Ireland; she was known across Scotland, and has left a few traces in Wales too. It seems entirely likely that she was also worshiped in Cornwall. And here’s the clincher: Pagan Brigid (and thus by default her Christian usurper) is particularly associated with sacred wells…

It’s as clear as water. Long, long before the time of Christ, there would have been two dank little cavities, lined with stones and glittering with goblins’ gold – one in a shallow cleft on the Cornish coast, the other above a streamlet in a long reach of marshy land in the west of Ireland. The precise hopes and sorrows that people brought to these watery spots back then are unknowable – though chances are they weren’t so different from our own. But it seems quite reasonable to suppose that the obeisance they offered at these two springs, 400 kilometres apart, was directed towards local variations of the same fecund female spirit. One place ended up walled off and abandoned, briefly pressed into service to supply nearby cattle troughs in the mid-twentieth century, then forgotten again. The other got a set of Millennium flowerbeds and a carpark. But stiff green reeds still grow near both wells.

© Tim Hannigan 2024